This story is based on my experience with scaling my Rails application - Kastio. Kastio application is going through its growth phase, and experiences occasional spikes in traffic.

How much scaling are we talking about

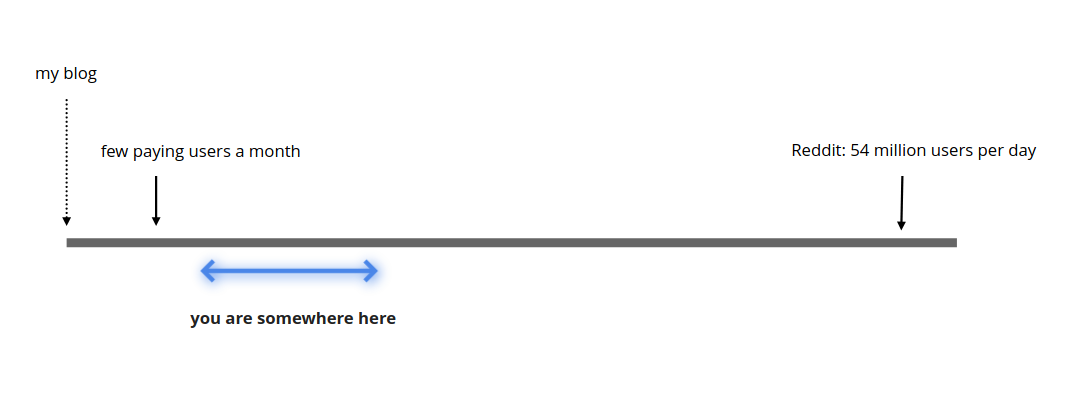

In terms of magnitude, scaling means different things to different people. Our situation is somewhat like this:

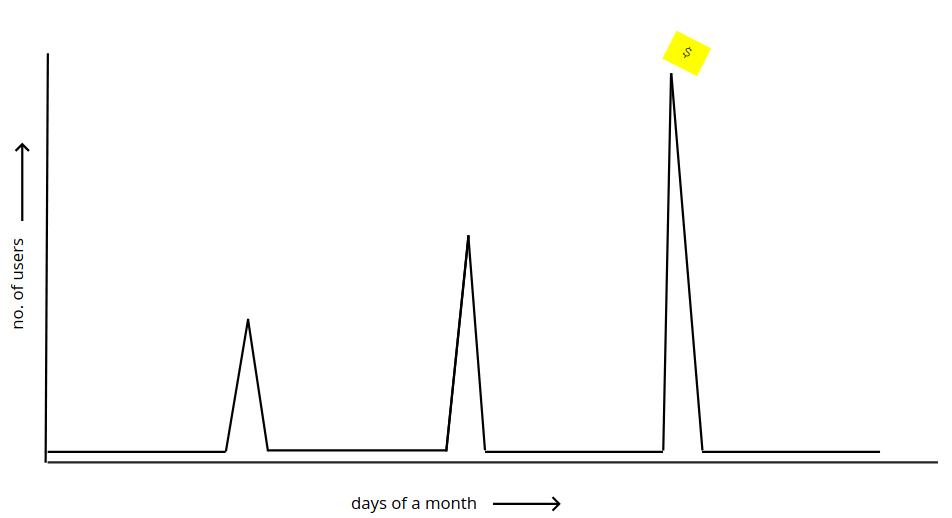

And our traffic looks somewhat like this:

The traffic spikes are a bit predictable - we can tell when they are about to happen. We can’t tell the traffic volume accurately, in requests per seconds, but we usually have a sense of the number of users arriving.

I like to call this kind of scaling requirement as ‘spike scaling’ or ‘sudden scaling’ or sometimes ‘ad-hoc scaling’. Tell me if there is a better or more established term.

This article may be useful if you are in a similar situation.

The constraints

Its important to think of the constraints too while approaching such a technical problem. If you had surplus funds, sufficient time, and an optimal codebase, the challenge would be rather uninteresting. Here were some of my constrains -

Costs

Kastio is a self financed small business. There is venture capital involved, and there is no option to make heavy upfront investments. Costs need to be kept under control.

However, the additional load comes with the promise of revenue. Making investments in infrastructure can work if the maths is right. Basically, the rise in costs should be proportional (at most) to the revenue generated.

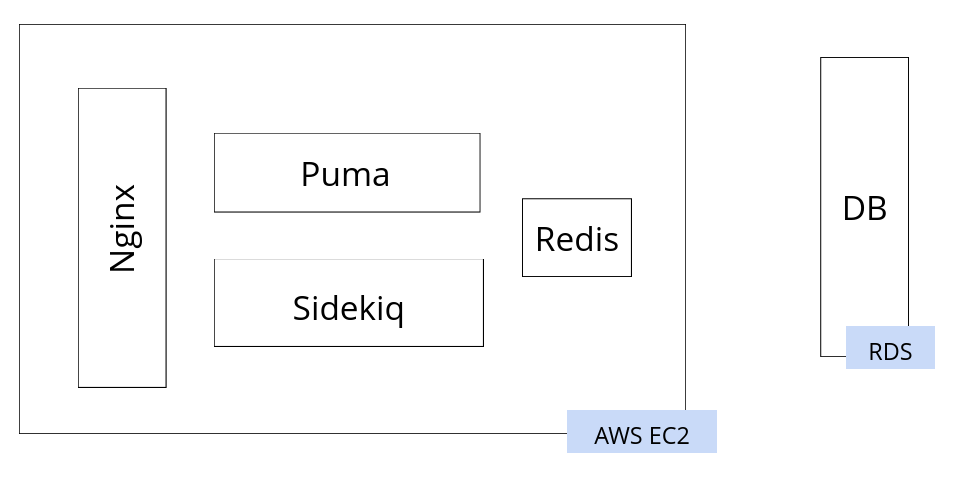

Existing architecture

Kastio is a Ruby on Rails application, with a fairly common setup:

All the components except the database are hosted on a single large EC2 instance. The database is hosted with Amazon RDS.

This is a farly good setup, and had served the business well for many years. For any production Rails application with positive revenues, this is a great starting point. After Heroku perhaps - if for some reason Heroku doesn’t suit you. I have some critical opinions on RDS, and despite that, I think this is quite good.

This setup serves well as long as you have even traffic (not low traffic). Scaling can happen vertically - increase the size of the EC2 instance whenever needed. While the traffic remained uniform, the instance was reserved to keep the costs in control. It is easy to monitor and maintain. Backups are simple, the learning curve is low, deployments are easy, restarts are easy. Its also easy to achieve dev-prod parity (or staging-prod parity).

I’d like to insist this is a very viable setup for many businesses. Many businesses earn steady revenues out of a stable (sometimes small) number of customers. The value (and revenue) comes from what the software does, and not from the number of users it has. My previous project, which was a B2B healthcare application, ran a similar setup for years while we grew from zero to hundred employees.

However, if the traffic is not uniform, vertical scaling becomes expensive. We would need to increase the server size to match peak capacity. And once the traffic comes down, all the extra capacity goes waste. In such a situation, we need to be able to increase and reduce capacity as needed, and preferably automatically. To achieve that, people often try horizontal scaling. We increase and reduce the number of server instances (or components), and configure them properly to work together.

That is not easy to achieve in this setup. We can’t add copies of this server, because the Nginx and Redis have to remain single. We need to increase the number of Puma instances by a lot, and the Sidekiq instances by a little. The architecture needs to change.

Time and team

Time was an important constraint, but not an extreme one. The business knows about bigger clients a few weeks in advance, and its the big clients that bring big traffic. And then there were big clients spread over a few months. Time seemed usually enough (but was not).

Kastio is a two developer business, and clients usually also come with feature requirements. Otherwise too its an active project, and there is always some work that seems more urgent than the scaling effort.

All in all, this means the scaling effort is allowed to be big overall, but should be executed in small chunks. We can never spare more than a few days on scaling. It should be done in phases. (At the time of writing, the third phase is in progress)

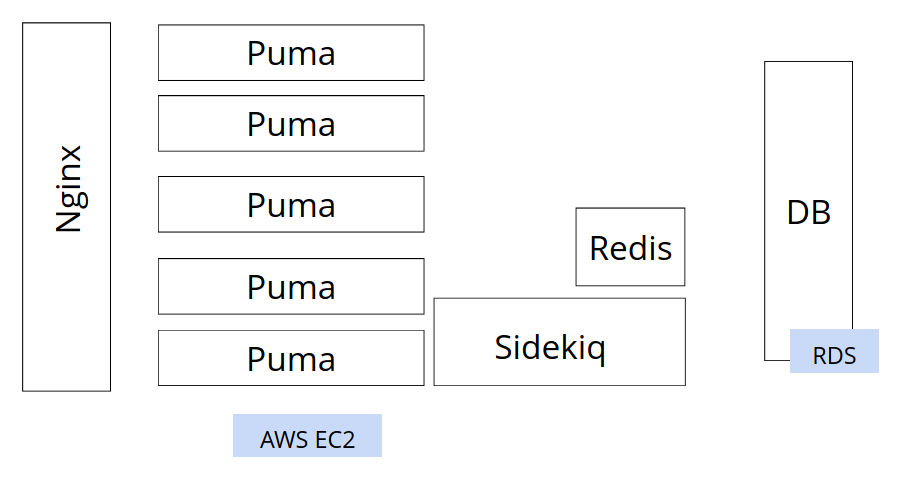

The first phase

The goal in this phase was to enable horizontal scaling, and scale enough to be stable during peaks. To get to an infrastructure that looks like this:

The idea being, I should be able to add Puma instances as traffic increases - manually. The other entities (the Db, Redis etc) would also be separate, and they would be scaled vertically if needed.

And then, we’d conduct load tests to get some sense of the numbers. Like how many Puma instances we’d need. Or what thread count should be used on each Puma. Or what our peak requests per second might be.

The time constraint was a little tough this time, so this looked quite a handful.

The arithmetic and the load testing

Here are some rough numbers I used as a starting point:

No. of users expected: 3000

Peak viewers: 1500 (assuming)

Response time: 500 ms (bad average)

No. of Puma threads: 15 (assuming 15 is not too much)

No. of Puma workers: 10

We can handle 15 * 10 = 150 requests at a time

The next 150 wait for 500ms

Batches in waiting: 1500/150 - 1: 9

The last batch waits for 9 * 500ms: 4.5 seconds (Not so bad !)

No. of dual core VMs needed: 10/2 ⇒ 5 (each can run two Puma workers

So if I started with five Puma instances, the worst response times I’d get would be around 5 seconds. This is not great, but no so bad either. If I added five more, this time would come down to better levels.

A more educated way to do this analysis is by bench-marking. The most popular metric people use is the 99 percentile time. That is the response times observed by the user at the 99 percent position in the wait list. That way, the above 4.5s is the 90 percentile time.

The biggest problem with the above calculations is the dependence on response times. In my app, the variation in response times is huge. Some endpoints were not optimal at all, some were acceptable. If there were a lot of requests hitting the slow endpoints, the results will change widely.

Therefore, instead of load testing on requests, I decided to try load simulation. For this simulation, a script would run the browser, and open a few pages within. Then click a few buttons here and there, and then logout. And we’d run a few hundred instances of this script, and then a few thousand. That way, we’d know -

- Whether the site is going down

- Does the site feel responsive (by checking manually)

- How are the Puma instances behaving

(This was not a good strategy)

The site went down, after everything

In short, because:

- Nginx also needs to scale

- Database also needs to scale

- Deployed architecture should match request profile

The details are as follows -

Nginx needs to scale

The Nginx we install on Ubuntu, by default, has connection limits. Its 768 per worker

events {

worker_connections 768;

# multi_accept on;

}

Since we have two workers by default, the limit effectively is 1536. This becomes important when we run Nginx in reverse proxy mode, because then, Nginx doesn’t control how long each request is going to take. Once the number of requests to slow endpoints start touching 1600, Nginx will give up.

One of the most frequently hit endpoint in Kastio is the heartbeat. Every user having opened the main page sends heartbeat requests at a definite frequency. The endpoint is fairly performant, but its quite likely that all these heartbeat requests get synced up across few thousand users, and Nginx gets choked.

This limit can be increased, but not drastically. The open file limit on the OS will also need to be increased. And then, all these configuration changes need to be load tested. A more sensible strategy is to increase the number of workers, and increase the VM size. Or try something like AWS load balancer

Database needs to scale

Our RDS instance got choked by connections, which lead to a crash. Any horizontally scaled system runs this risk. We have a connection pool within a single Puma instance, but once the number of instances start increasing, there is no limit on the number of connections they may throw at the Db. At that point, we were running a 4Gb instance for the DB, which has a connection limit of 341.

We could also scale up the database instance so the connection limits are higher. That’s what we did at that point (during the firefighting effort). AWS also has a service called the AWS Proxy that can do the global pooling for us. It makes better sense to use it.

I eventually found that there was this one API endpoint that suffered from the infamous N+1 problem. And it also happened to be one of the most frequently accessed endpoint.

Another aspect to this is price. Database hosting is expensive, generally the most expensive part of the setup. It’s not prudent to scale it up very liberally. Having some kind of arbitrary connection limit is important. The application code should then be optimized from database access point of view.

Deployed architecture should match request profile

Requests in our app have varying loads. Some (like heartbeats) are extremely frequent, and performant. There are others that are moderately frequent, not so performant but critically important (like the one that drowned the DB). Some are important, but not so frequent.

Some of this information is available from APM tools like NewRelic. Importance can be determined by product owner.

Now the idea is, our deployed infrastructure should reflect this variance. The most critical endpoints should be served from redundant servers. The most frequent one’s should be given the most capacity. And if their load is many orders of magnitude higher than the rest, its better to isolate them. Thus, they can’t overwhelm the rest of the setup, and fail alone if at all.

We did end up separating the heartbeats out to an entirely separate pipeline, right from DNS. That helped a lot. The database was still the same, so, after everything else, the only remaining bottleneck was the database.

Phase 1 conclusions/lessons

We went through a lot of pain on the night of 25th September. There were three spikes that night, and the site went down every-time. New bottlenecks were revealed each time. A few quick fixes worked for the first and second time, but the third time it was long and bad. That was when the database had choked and the site went down entirely and completely - the other times it was partly functional or slow.

Focusing on Pumas alone in preparations was the biggest mistake. And it is not unusual to run on the assumption given the amouont conventional wisdom against scalability of Rails applications.

Then, using Puppeteer simulations for load testing was a bad idea. The simulations ran fine, but the reporting was nowhere close to what professional testing tools can give. It definitely missed some insights that would have been useful in the planning. A Puppeteer based load testing tool is a good idea, on paper, but it needs a lot more time and effort to prefect